This article is part of our May 2020 special issue. Download the full issue here.

Reference

Catinean A, Neag AM, Nita A, Buzea M, Buzoianu AD. Bacillus spp. spores—a promising treatment option for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):1968.

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare rifaximin followed by a nutraceutical or low–fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet to stand-alone therapy with a spore-based probiotic (MegaSporeBiotic) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) without constipation.

Design

A nonblinded, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical study. Participants were randomized to 3 groups:

- G1, in which participants received a 10-day course of rifaximin (1,200 mg) followed by a 24-day course of a nutraceutical containing Bifidobacterium longum W11, soluble fiber, and vitamins B1, B2, B6, and B12.

- G2, in which participants received a 34-day course of Bacillus spp probiotic (Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus indicus HU36™, Bacillus subtilis HU58™, Bacillus clausii, Bacillus coagulans, all from the MegaSporeBiotic brand).

- G3, in which participants received a 10-day course of rifaximin (1,200 mg) followed by a 24-day low-FODMAP diet.

The researchers obtained outcome measures at baseline, day 10 (for groups G1 and G3), day 34, and day 60.

Participants

This study included 90 patients with IBS without constipation based on Rome III criteria. Patients were aged 18 to 75 years with a normal colonoscopy in the last 5 years, blood counts within reference values, and normal fecal calprotectin. Patients with documented food allergies, gluten intolerance or celiac disease, diabetes, thyroid disease, intestinal inflammatory disease or other organic diseases, eating disorders (anorexia or bulimia), probiotics 1 month before the study, antibiotic treatment in the previous 6 months, or specific diets were excluded.

Study Parameters Assessed

Researchers evaluated patients based on the IBS severity score (IBS-SS), quality of life for IBS patients (IBS-QL), and a rectal volume sensation test.

Key Findings

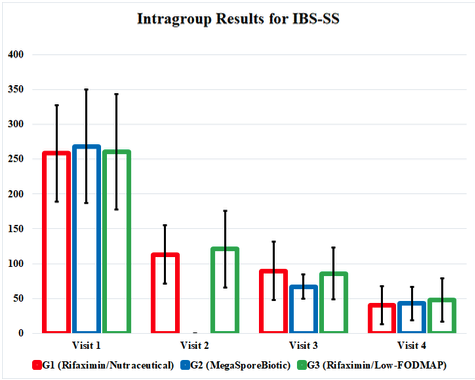

IBS-SS improved at each outcome measurement for G1, G2, and G3 and, interestingly, improved equally by the end of the study. The MegaSporeBiotic group, G2, did have earlier symptom improvement at the 3rd visit (day 34). Quality-of-life scores and the rectal volume sensation testing also improved in every group, with similar outcomes in each group.

Practice Implications

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common disorder that affects approximately 10% of the population, with significant gaps in reliable and cost-effective treatment strategies.1 Our understanding of pathophysiology is rapidly expanding using systemic biology. The current proposed model is a complex web of dysfunction of the gut microbiota, altered intestinal permeability, altered motility, gastrointestinal (GI) immune-cell activation, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal gut-brain interactions.2 Rifaximin first emerged as an effective treatment option to alter GI microbiota in 2011 with the TARGET trial, which eventually led to the FDA approval of rifaximin as a treatment for IBS with diarrhea in 2015.3 This study aims to show that nonantibiotic therapy may also be effective to treat IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) through the alteration of the microbiome via a spore-based probiotic.

One of the most exciting aspects of this study is the cost efficacy of spore-based probiotic versus rifaximin.

This study does contain multiple significant limitations, many of which the authors acknowledge. These include a lack of blinding and placebo, moderate rather than severe symptoms at baseline, a lack of breath testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and the use of Rome III rather than Rome IV criteria. The researchers used Rome III because this study started prior to Rome IV, and the authors note that 90% of participants also met the new criteria.

There are additional limitations not discussed by the authors. The first, and perhaps most important, is that the rifaximin treatment group was undertreated in both dose and duration. The current universally accepted dosage of rifaximin for IBS-D is 550 mg 3 times daily (1,650 mg total daily dose) for 14 days.4 This study used 1,200 mg total per day for 10 days, which is 52% of the effective dose. This introduces a significant source of outcome bias toward the spore-based probiotic intervention.

Improved outcome measures could strengthen this trial. First off, the authors used a rectal volume sensation test at baseline and at each visit. This testing is invasive, uncomfortable, and poorly supported in the literature as an outcome measure for IBS-D.5 In place of rectal volume sensation testing, a noninvasive, 3-hour lactulose breath test would improve study design. This would have allowed the authors to include patients with SIBO only, or could have stratified responders in each treatment group based on SIBO status. Rezaie et al found that patients with a positive lactulose breath test for SIBO do respond significantly better to rifaximin therapy compared to IBS-D patients with a normal breath test.6 Including 3-hour lactulose breath testing in this study would have clarified which patients were the best candidates for spore-based probiotic treatment versus rifaximin therapy.

Using 2 treatment groups (rifaximin/low-FODMAP diet versus spore-based probiotic) or 2 treatment groups and a placebo group would have improved the clarity of the results. Blinding could remove another source of bias; however, it is impossible to blind therapeutic diet versus usual diet, and this is an ongoing challenge in nutrition research.

The impact of the therapeutic interventions in this study was buried in confusing and cumbersome tables, so I have highlighted positive results in a graph form that illustrates the study’s findings. This graph represents the study results and shows us how effective these therapies are compared to each other. It also highlights the fact that all 3 treatment groups continued to improve even after interventions were discontinued at visit 3 (day 34).

One of the most exciting aspects of this study is the cost efficacy of spore-based probiotic versus rifaximin. The dose of rifaximin used in this study costs approximately $1,300, and the recommended dose is closer to $2,000. Insurance coverage often requires multiple drug failures and prior authorizations, if the treatment is covered at all. The dose and duration of the spore-based probiotic used in this study retails for $55. This represents a significant advantage of spore-based probiotic therapy. The authors did not report side effects or participant dropouts, so it is difficult to calculate these factors into a cost-benefit ratio.

It should also be noted that outcomes were similar for spore-based probiotic therapy versus the treatment group following a low-FODMAP diet. The low-FODMAP diet has emerged as an effective dietary strategy to treat IBS-D.7 While it is exciting to have an effective dietary tool for IBS, this diet is highly restrictive and has wide-reaching psychosocial and nutritional implications.8 In my experience, the low-FODMAP diet is a more stressful diet compared to other, perhaps even more restrictive diets, because food choice is not intuitive. Patients must be constantly using handouts and apps and, thus, must become hypervigilant to successfully follow this diet. In this regard, spore-based probiotic therapy offers a significant advantage.

Conclusion

While this study has multiple methodological issues that introduce bias, it is important to acknowledge that the results of this study improve our understanding of treatment options for IBS-D. Spore-based probiotic therapy as a standalone therapy was associated with improvements to IBS severity scores, quality of life, and rectal volume sensation that were equal to those associated with rifaximin therapy followed by low-FODMAP diet or probiotic therapy. Symptoms continued to improve with all 3 interventions after treatment was discontinued, as evidenced by improved IBS severity scores at day 60 versus day 34 when treatment ended. The most significant error in the study was the inadequate dose of rifaximin for treatment. Despite this, spore-based probiotic therapy offers a significantly easier treatment at less than 5% of the cost of rifaximin. Further research is needed before claiming that spore-based probiotic therapy is as effective as rifaximin, but it may certainly be considered when navigating treatment options with IBS-D patients.