In 2014, the FDA issued a proposed rule titled, “Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels.” This means in the next few years, everyone in the United States will need to learn to read new food and supplement labels to find out nutritional information for everything from breakfast cereals to ice cream to multivitamins. This article gives readers a head start.

Introduction

In the next few years, everyone in the United States will need to learn to read new food and supplement labels to find out nutritional information for everything from breakfast cereals to ice cream to multivitamins. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is updating the regulations that dictate which label information is mandatory in an effort to inform consumers of key information so they can make healthful food choices.

In March 2014, FDA issued a proposed rule entitled, “Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels” and received public comment until August 2014. The agency is currently reviewing thousands of comments and preparing to release a final rule in the first quarter of 2016. The final rule will designate the amount of time food and supplement companies have to make the necessary changes to the nutrition and supplement facts label to comply with the new regulations. As these sweeping changes near, it is important for consumers and their healthcare practitioners to be aware of some of the anticipated changes because they undoubtedly will require clinician and consumer education to mitigate any confusion.

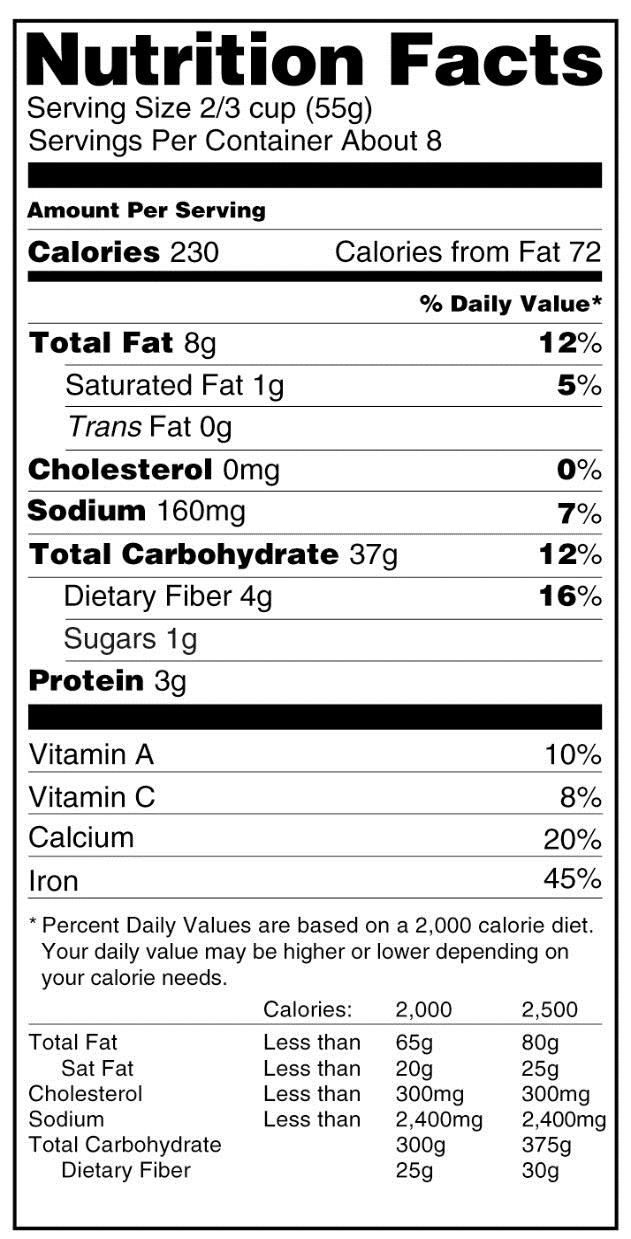

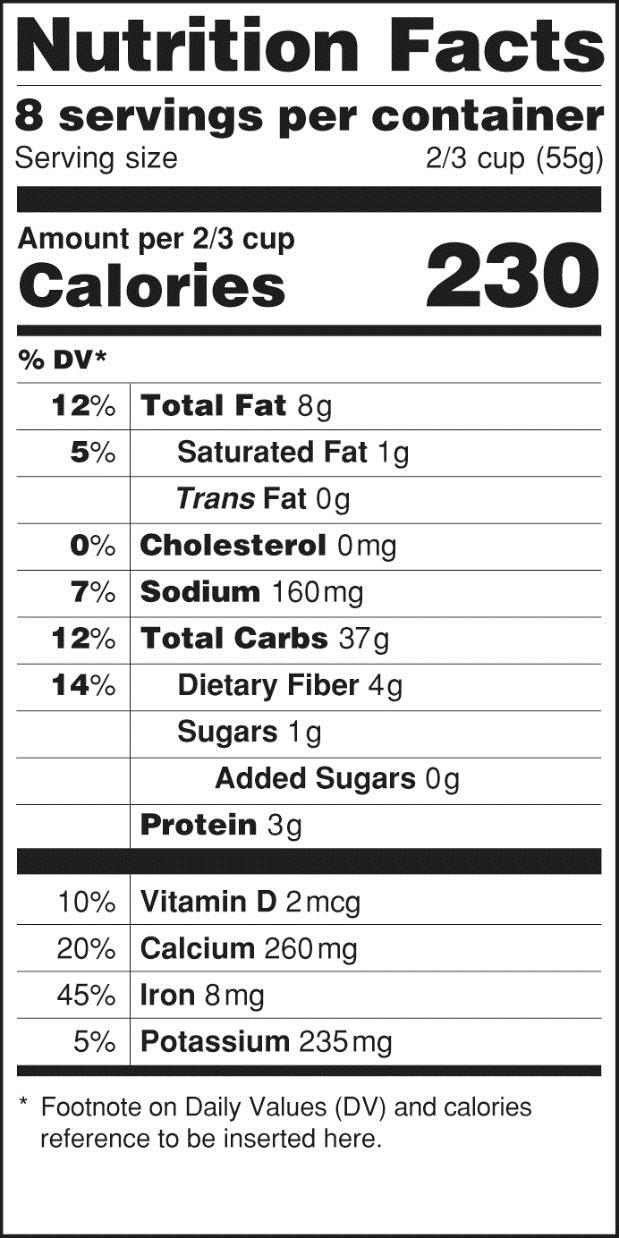

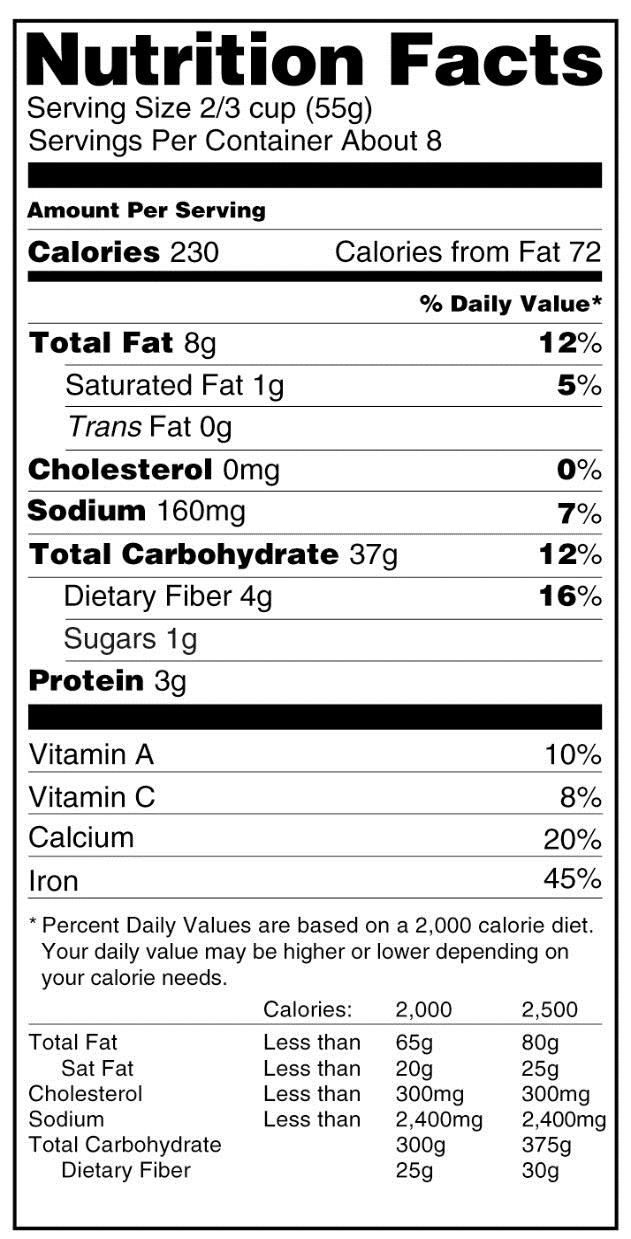

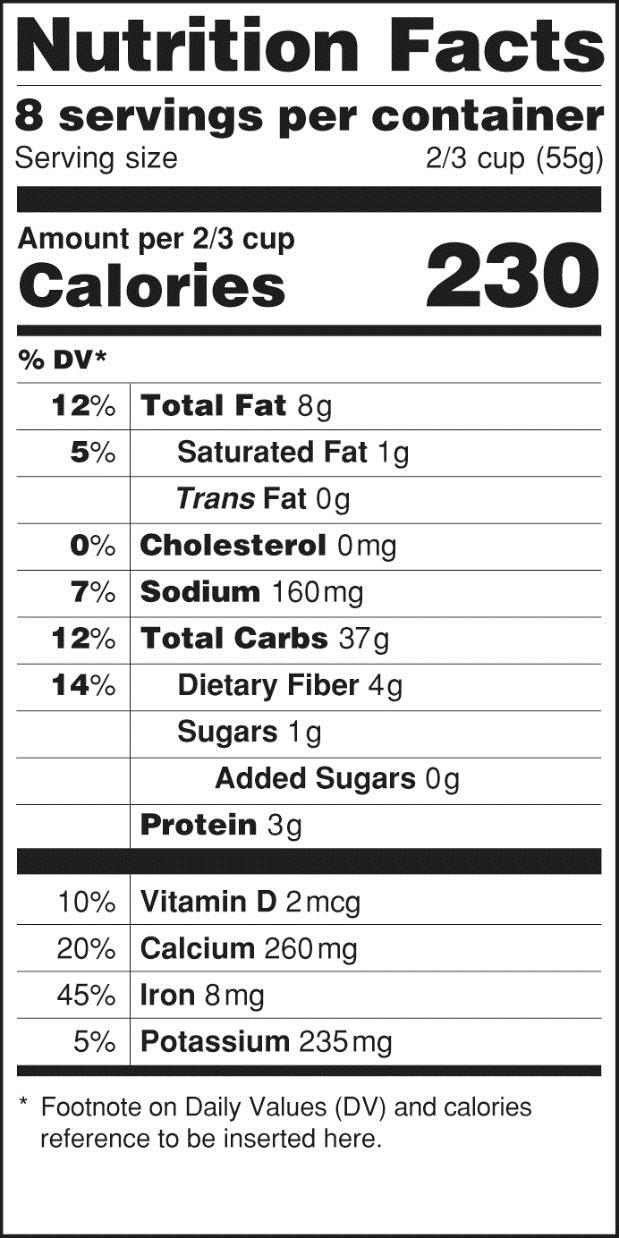

The proposed change that has received the most attention in the media is the requirement to declare added sugar on nutrition labels, based on recent dietary recommendations advising Americans to reduce calorie intake from added sugars.1 FDA also plans to remove the declaration of calories from fat because current science shows that for risk of chronic disease, the type of fat is more relevant than total fat. With respect to label format, FDA intends to increase the prominence of the “Calories” listing, as well as the number of calories declared on the label. Additionally, the number of “Servings per container” listing will be more prominently displayed to help consumers more accurately identify the number of calories in a product. Examples of the current and proposed labels are provided in the Figure.

Beyond these changes, there are a number of planned updates that have been less publicized but are equally relevant to consumers. Some are not easily identifiable and could go unnoticed without extensive educational initiatives. A few highlights of the proposed rule changes that healthcare professionals should be aware of when they provide nutritional guidance to patients are provided below.

Reference Daily Intakes

FDA proposes to update the Reference Daily Intake (RDI) guidelines, which are used to calculate the percentage of daily value (DV), for nutrients on food and supplement labels. Currently, the RDIs are based on the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) established by the US National Academy of Sciences in 1968. FDA plans to use more updated RDA values (or “adequate intake” measures where RDAs are not available) that were set by the Institute of Medicine between 1997 and 2011. For comparison, a list of the current and proposed RDIs is presented in the Table.

Table. Current and Proposed RDIs for Nutrition Labelinga |

Nutrient | Current RDIs | Proposed RDIs |

Vitamins |

Biotin | 300 µg | 30 µg |

Choline | 550 mg | 550 mg |

Folate | 400 µg | 400 µg DFE |

Niacin | 20 mg | 16 mg NE |

Pantothenic acid | 10 mg | 5 mg |

Riboflavin | 1.7 mg | 1.3 mg |

Thiamin | 1.5 mg | 1.2 mg |

Vitamin A | 5,000 IU | 900 µg RAE |

Vitamin B6 | 2.0 mg | 1.7 mg |

Vitamin B12 | 6 µg | 2.4 µg |

Vitamin C | 60 mg | 90 mg |

Vitamin D | 400 IU | 20 µg |

Vitamin E | 30 IU | 15 mg |

Vitamin K | 80 µg | 120 µg |

Minerals |

Calcium | 1,000 mg | 1,300 mg |

Chloride | 3,400 mg | 2,300 mg |

Chromium | 120 µg | 35 µg |

Copper | 2.0 mg | 0.9 mg |

Iodine | 150 µg | 150 µg |

Iron | 18 mg | 18 mg |

Magnesium | 400 mg | 420 mg |

Manganese | 2.0 mg | 2.3 mg |

Molybdenum | 75 µg | 45 µg |

Phosphorus | 1,000 mg | 1,250 mg |

Potassium | 3,500 mg | 4,700 mg |

Selenium | 70 µg | 55 µg |

Zinc | 15 mg | 11 mg |

aBased on a 2,000 calorie intake for adults and children 4 or more years of age

Abbreviations: DFE, dietary folate equivalents: 1 DFE=1 µg food folate=0.6 µg of folic acid from fortified food or as a supplement consumed with food; IU, international unit; NE, niacin equivalents: 1 mg niacin=60 mg of tryptophan; RAE, retinol activity equivalents:1 RAE=1 µg retinol, 12 µg beta-carotene, 24 µg alpha- carotene, or 24 µg beta-cryptoxanthin; RDI, reference daily intake.

These proposed updates will result in labeling changes, formulation changes, or both for food and dietary supplements. Consumers may find that products containing the same amount of a given nutrient will now be labeled as providing more or less of the percentage of DV. A dramatic example of this is the proposed RDI for biotin (vitamin B7), which will decrease 10-fold from 300 µg to 30 µg. This means a product currently labeled as providing 100% of the DV for biotin will in the future be labeled as providing 1,000% of the DV.

In some cases, the percentage of DV on the label may not change, but the absolute amount of the nutrient will. As an example, products currently labeled as containing 100% of the DV for vitamin B12 contain 6 µg. FDA proposes to reduce the RDI of vitamin B12 to 2.4 µg, which means consumers continuing to seek products that provide 100% of the DV may unknowingly consume lower levels of vitamin B12. This may be an issue for older individuals, who have a reduced capacity to absorb dietary vitamin B12 and thus are at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency. In fact, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans encourage individuals 50 years and older to obtain adequate vitamin B12 by consuming foods fortified with vitamin B12, such as fortified cereals or by taking dietary supplements.1 Because vitamin B12 deficiency is prevalent in vegetarians and vegans, an individual consuming a vegetarian or vegan diet may be at risk.2 It will be important for healthcare professionals to provide guidance on selecting the appropriate products to avoid deficiency in these patients.

Units of Measure

In addition to numeric RDI values, FDA plans to change the units of measure for several nutrients. International units (IU)—currently used as the unit of measure for vitamins A, D, and E—will be updated to metric units. For vitamin A specifically, the proposed unit of measure is microgram (µg) retinol activity equivalents (RAE), where 1 RAE equals 1 µg retinol, 12 µg beta-carotene, 24 µg alpha-carotene, or 24 µg beta-cryptoxanthin. These conversions account for the differences in vitamin A activity between provitamin A carotenoids and preformed vitamin A. Likewise, the unit of measure for niacin will also change from milligram (mg) to mg niacin equivalents (NE) where 1 mg niacin equals 60 mg tryptophan. As product labels transition to incorporate the new units of measure, educational initiatives will be needed to help consumers understand the changes.

Folic Acid/Folate

Two major changes are proposed for folate and folic acid. First, the unit of measure will be changed from µg to µg Dietary Folate Equivalents (DFE) while maintaining the same numeric value for the RDI (400 µg DFE). Based on the greater bioavailability of folic acid compared to food folate, the contribution of folic acid from food or dietary supplements labeled to be consumed with food to the DFE is subject to a conversion factor of 1.7 or 2.0 from dietary supplements not labeled to be consumed with food. What this means is a dietary supplement labeled to be consumed with food that currently lists 400 µg folic acid would instead list the same amount as 680 µg DFE (ie, 400 µg folic acid x 1.7 conversion factor=680 µg DFE), which is 170% of the proposed RDI. Conversely, a manufacturer could lower the amount of folic acid in dietary supplement products to 240 µg folic acid (providing 400 µg DFE) in order to maintain a 100% DV declaration on the label (240 µg folic acid x 1.7 conversion factor=400 µg DFE [approximately]).

Given that the 'Nutrition Facts' label has not changed since it was first introduced over 20 years ago, an update is much needed to reflect advances in nutrition science and to provide more useful information to consumers.

A potential consequence of this proposed change is that individuals may unknowingly consume less than the current RDI of 400 µg folate/folic acid if they select products solely on the basis of providing 100% of the DV. Several health organizations—including the US Centers for Disease Control, US Public Health Service, and March of Dimes Foundation—recommend 400 µg folic acid, the current RDI, in addition to whatever amount of naturally-occurring dietary folate consumed for women of childbearing age to reduce the risk of having a baby with neural tube defects.

FDA also plans to change the permitted terminology for folate and folic acid on nutrition and supplement facts labels. Currently, the terms folic acid, folate, or folacin may be listed on the nutrition or supplement fact label. FDA proposes to only allow the use of the term folic acid for the labeling of dietary supplements with the term folate to be used on conventional food labels for foods that contain either folate only or a mixture of folate and folic acid. The term folacin will no longer be used. These changes represent an effort by the agency to distinguish between folic acid (pteroylglutamic acid) and naturally occurring folates in food (various polyglutamate forms). However, while folic acid is used as an ingredient in dietary supplements and to fortify foods such as flour, several dietary supplements on the market contain synthetic folates that include (6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, calcium salt, (6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, or glucosamine salt. Since these folate ingredients do not meet the definition of folic acid or naturally occurring folate, the proposed rule would mean that their amount and contribution to the percentage of DV of folate/folic acid cannot be communicated on product labels. Consumers taking products with synthetic folates as alternatives to folic acid will most likely be confused by these labeling restrictions.

Nutrients of Public Health Significance

Vitamin D and potassium are recognized by FDA as nutrients of “public health significance” in the proposed rule. This recognition is based on the beneficial effects vitamin D and potassium have on bone health and blood pressure, respectively; the high prevalence of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and hypertension among the general population; and the inadequate intake of both vitamin D and potassium in the US population. As nutrients of public health significance, vitamin D and potassium will be mandatorily declared on nutrition and supplement facts labels to help consumers make informed choices on how take in enough of these important nutrients. With mandatory labeling, consumers will be aware of all dietary and supplemental sources of vitamin D and potassium when they are present in a given product.

With respect to other nutrients, the current mandatory requirement for listing calcium and iron will not change, while the listing of vitamins A and C will no longer be required (but may be made voluntarily) because these vitamins are no longer considered by the agency to be nutrients of public health significance. Although overt deficiency is not common in the United States, intakes of vitamins A and C continue to be inadequate. Government data show that 45% of American males and females over 2 years of age (excluding pregnant and lactating women) do not achieve the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) for vitamin A from foods.3 Even when dietary supplement use is considered, approximately one-third of these Americans still do not meet the EAR. For vitamin C, 37% of Americans consume levels below the EAR from food; this number decreases to 25% when dietary supplement consumption is included.3 The removal of mandatory labeling of vitamins A and C will make it more difficult for consumers to identify dietary sources of these vitamins.

Dietary Fiber

Another important topic discussed in the proposed rule is dietary fiber. For the first time, FDA has proposed a formal definition of dietary fiber for labeling purposes. The definition includes nondigestible carbohydrates (with 3 or more monomeric units) and lignin that are intrinsic and intact in plants. Isolated and synthetic nondigestible carbohydrates (with 3 or more monomeric units) will also qualify, but only if (1) FDA grants their inclusion in the definition in response to a petition demonstrating that such carbohydrates have a physiological effect(s) beneficial to human health or (2) they are the subject of an authorized health claim.

While this definition will not affect traditional fiber sources in the diet, it may impact the labeling of products containing innovative fiber ingredients. Consumers who do not get enough fiber from traditional sources may look to alternative fiber ingredients added to foods or dietary supplements to meet their needs. Under the proposed rule, it will be more difficult to identify such ingredients as sources of fiber. The health claim approval process is onerous; only 2 isolated fibers—beta-glucan soluble fiber and barley beta-fiber—are currently the subject of authorized health claims in the United States. Additionally, the petition process that FDA has proposed for dietary fiber is unclear. For example, the agency has not provided clear guidance on what would be considered a beneficial physiological effect.

Dietary fiber is well recognized for its role in colon health and laxation, and there is also evidence of its involvement in reducing the risk of coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic diseases.4 However, intake of dietary fiber is very low in the US population. Recently, the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee indicated that the average intake of dietary fiber is half of the recommended levels, concluding that fiber is a nutrient of public health concern.5 Considering these low intakes, having a wide range of options is useful for consumers to help obtain adequate amounts of fiber. The restrictive proposed definition of dietary fiber will narrow the range of products that may be labeled as providing dietary fiber; therefore, consumers may need guidance from healthcare professionals about fiber sources that can meet their needs.

Conclusions

Given that the “Nutrition Facts” label has not changed since it was first introduced over 20 years ago, an update is much needed to reflect advances in nutrition science and to provide more useful information to consumers. Food and dietary supplement labels can be a valuable resource for healthcare professionals when they counsel patients who have specific medical or nutritional needs or are simply looking for healthy choices. Therefore, it is important that practitioners be aware of and understand the forthcoming changes to nutrition and supplement labels so that they can provide informed guidance to their patients. The proposed changes will also provide an opportunity to encourage individuals who do not look at labels to start paying attention.