Reference

Imai S, Kajiyama S, Kitta K, et al. Eating vegetables first regardless of eating speed has a significant reducing effect on postprandial blood glucose and insulin in young healthy women: randomized controlled cross-over study. Nutrients. 2023;15(5):1174.

Study Objective

To explore the effect of eating speed and eating order on postprandial blood glucose levels in healthy females

Key Takeaway

Consuming vegetable and protein components of a meal first significantly lowers glycemic impact.

Design

This study used the same group in a cross-over design where all participants consumed identical meals with 3 different eating speeds and food orders.

Participants

Twenty-one students at the Kyoto Women’s University took part in this study between April and July 2022.

Three of the 21 participants did not complete the study. Of the 18 women who completed the study, the average age was 21.3 years, average BMI was 19.6 kg/m2, and HbA1c was 5.2 ± 0.3%.

None of the participants were pregnant, had eating disorders, had metabolic diseases, were following specific diets, or were taking medications or supplements that would affect blood sugar, insulin, or lipid levels.

None of the participants had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or a family history of the condition.

Intervention

Identical meals were eaten on 3 separate days, each 1 week apart, with different eating patterns on each occasion. Two meals were eaten slowly with either vegetables first or carbohydrates first. The third meal was eaten quickly with vegetables first.

All the meals consisted of vegetables (tomato and broccoli with sesame oil), fried fish, and boiled white rice. The slow meal was carefully timed and stretched to 20 minutes. The fast meal was eaten in half that time.

Study Parameters Assessed

Blood samples were collected at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after the meal and tested for blood glucose, insulin, triglycerides (TG), and free fatty acids (FFA). The area under the curve (IAUC) was calculated for glucose and insulin.

Primary Outcome

The study was designed to ask whether eating speed or meal order affected postprandial glucose or insulin levels.

Key Findings

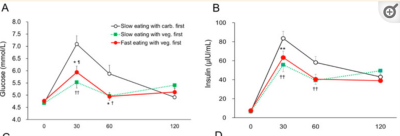

Eating the vegetable portion of the meal first and eating slowly had a significant effect on postprandial blood glucose at 30 minutes and 60 minutes compared to all other eating patterns.

At 30 minutes postprandial:

- slow eating with carbohydrates first: 7.09 ± 0.34 mmol/L,

- fast eating with vegetables first: 5.94 ± 0.24 mmol/L (P<0.05).

- slow eating with vegetables first: 5.53 ± 0.25 mmol/L, (P<0.01)

- slow eating with carbohydrates first: 5.88 ± 0.34 mmol/L

- fast eating with vegetables first: 4.95 ± 0.18 mmol/L

- slow eating with vegetables first: 4.97 ± 0.16 mmol/L (P<0.05)

Note: At 60 minutes, there was no difference between slow or fast eating in those who ate vegetables first.

Postprandial insulin concentrations were significantly lower when vegetables were eaten first than when carbs were eaten first.

Transparency

The study was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research KAKENHI (20K11569) of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). The authors state that they, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article. The authors declare that although they are affiliated with a department that is supported financially by a pharmaceutical company, the authors received no current funding for this study and this does not alter their adherence to all the journal policies on sharing data and materials.

Practice Implications & Limitations

Over the last decade, a new approach to dietary management of blood sugar has entered the medical literature. The new approach posits that the order in which we consume different foods in a meal plays a significant role in resulting blood sugar levels—far more than we might have guessed. This study is one of a series of reports that help advance our understanding.

Eating carbohydrates on an empty stomach has a far greater impact on blood sugar than eating the same foods during or after a meal.

Alpana Shukla et al published an earlier study on meal composition timing in 2019. In their study, participants were served a meal of grilled chicken, steamed vegetables, and a salad dressed with vinaigrette on 2 different days. On one of those days, they ate a standard-sized ciabatta before the meal. On another day, they saved the bread until after they had eaten everything else. Blood sugars peaked 40% lower if vegetables or protein were eaten first. Expressed another way, blood sugars rose 40% higher if the bread was eaten first.1

An even earlier study, led by Saeko Imai was published in 2014 and reported a significant impact by simply eating vegetables before carbohydrates in a group of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes both acutely and over a 2.5-year follow-up period. These studies were notable as they employed continuous glucose monitoring systems that were developed in 1999 and made obtaining and analysis of these complex data possible. The blunting of hyperglycemic episodes was more pronounced in those with diabetes than in those without.2

In a 2018 study, Nishino et al reported that saving carbs for last—after meat or vegetables—lowered blood glucose levels in healthy non-diabetic Japanese subjects.3

The idea that eating quickly and rushing through a meal is associated with greater risk of obesity first appeared in 2011 in a New Zealand nationwide survey.4 In 2014, a Japanese survey (N=56,865) reported that fast eating was associated with metabolic syndrome.5 A smaller 2012 survey said fast eating was associated with T2DM in men (N=2,050).6

There may be a reason this strategy has gained more attention in Japan than in the United States and has become an accepted dietary strategy for treating diabetes there.7 Japanese people and others of East Asian descent often have delayed insulin secretion, about half that of people of European descent.8 Thus, whether the extent of the difference in blood sugar is as dramatic in other populations is not clear.

The most likely explanation for the amelioration of postprandial blood sugar levels is that the high amount of fiber contained in the vegetables slows the digestion of carbohydrates eaten afterward. There is another possibility in this current study: The sesame oil in which the vegetables were cooked may have triggered the release of incretin hormones that increase insulin secretion and delay gastric emptying.9

Nevertheless, this is such a simple and easy-to-implement health intervention strategy, it behooves us to inform patients, especially those with diabetes, of the possible potential benefit.10

We should eat vegetables or protein before eating carbohydrates. If we do so, eating speed has little impact. By vegetables, we mean recognizable vegetables that, if cut in pieces, are still whole enough to name. Researchers have tried adding pureed vegetable to rice to achieve a similar amelioration without finding a benefit—which, sadly, probably means the tomato sauce on a slice of pizza doesn’t count.