Abstract

Menopause can be a challenge for women who suffer from unwanted symptoms, including insomnia associated with night sweats and hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and chronic urinary problems. In addition, for those contemplating hormone replacement therapy (HRT) while evaluating its use and the potential for aggravating side effects and medical risks, the information available to the public can be confusing.

Some hormonal changes that occur in menopausal women and andropausal men are associated with medical comorbidities like insulin resistance and obesity. Body weight affects hormone levels, and this paper will reference that link as it pertains to conditions affecting menopausal women. However, this topic deserves a more comprehensive review than this paper can provide.

Despite the successful use of nonhormonal treatments to alleviate menopausal symptoms,1 localized vaginal atrophy, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and chronic urinary problems continue for some women. This article will summarize the use of low-dose or ultralow-dose estradiol, estriol, estetrol, and oxytocin therapy as a potentially safe option for some of these women. It also will briefly review the use of micronized progesterone in opposing estrogen therapy. Before a discussion of the possible therapies, a review of the hormones used in menopausal women is essential.

Estrogen Hormones

In women, the 4 main naturally occurring estrogens are estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4). Following is an overview of each.

Estrone (E1)

After menopause, a reduction in estradiol levels occurs due to a decrease in production by the ovaries. What little estradiol is present after menopause comes primarily from peripheral conversion.2 Estrone becomes the dominant estrogen after menopause; it is produced through peripheral conversion of adrenal androstenedione by aromatase, primarily in adipose tissues, but also directly in the adrenal glands.3,4 Fatty breast tissue is a principal site of aromatase activity, but activity is also present in the brain, muscle, liver, and, minimally, the ovaries of a postmenopausal woman. Notably, the body stores estrone primarily in adipose tissue, so women with low body fat may have lower levels of estrone compared to women with normal body fat or women with a higher body mass index (BMI).5

Estradiol (E2)

Estradiol is primarily made in the ovaries. It is the most prevalent estrogen in the body during the reproductive years, is responsible for the development of female sexual characteristics, and prepares the body for pregnancy. Estradiol is a metabolite of testosterone and has been shown to participate in male sexual development in early life as well as adult male sexual function in later life.6 Estradiol plays an important role in bone density in men.7 The use of estradiol in the treatment of osteoporosis in menopausal women is an important benefit to discuss with patients when weighing the benefits and risks of HRT.

Finding the lowest dose of estrogen that benefits bone density is an essential component in the current environment of thoughtful prescribing of HRT. Research is attempting to establish the lowest dose of hormone therapy that patients can use to obtain a clinically significant and positive effect on a negative health deficiency—for example, introducing the lowest dose of estrogen therapy to counteract or improve a negative health marker such as low bone density. In a trial of transdermal low-dose estradiol (14 µg [0.014 mg]) for 2 years, a 2.6% and 0.4% increase occurred in lumbar and hip bone density, respectively (P<0.001). Trial participants also used 800 mg of daily calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D. There was no significant increase in the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia in the women using the hormone cream. It should be noted that 1 of the 417 women in the study developed hyperplasia.8

Estetrol and oxytocin offer unique and promising alternatives for practitioners, especially given their potential antitumor properties, although more studies are needed to verify the safety of these therapies.

Low-dose therapy, or “micro-dosing,” has also been shown to address vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes. In a stepwise fashion, 14 µg of daily transdermal estradiol cream was effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes in 50%, 70%, and 95% of women following 2, 4, and 12 weeks of use, respectively (P<0.001).9 No significant side effects were noted in the women using the estradiol cream.

In another study of 188 women using a 14 µg estradiol patch, only 8.5% of the hormone-treated group (16 women) had endometrial proliferation at the end of the study (P=0.06), and 12.2% (23 women) had vaginal bleeding (P=0.3). The researchers concluded that the estradiol and placebo groups had similar rates of endometrial hyperplasia and vaginal bleeding.10

The clinical goal would be to provide a type of estrogen replacement therapy that would result in minimal to no increase in serum estradiol levels until further research demonstrates whether the observed correlation between estradiol levels in menopausal women and risk of cancer is conclusive. The following is a summary of such research.

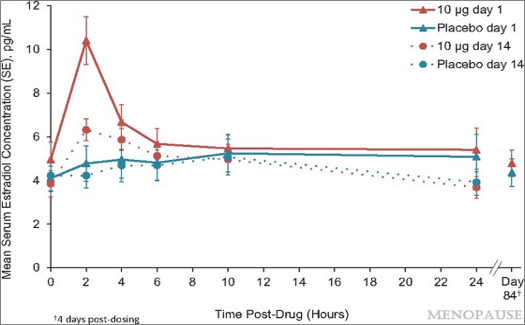

In a study using 50 µg (0.05 mg) of 17-β-estradiol intravaginal cream nightly, serum estradiol levels changed from 7.7 pg/mL to 9.7 pg/mL after 8 weeks of use (P=0.24).11 In another study using 25 µg (0.025 mg) of intravaginal estradiol, there was a sharp increase in serum estradiol levels within the first several hours of delivery, and levels remained elevated for 2 weeks. This was compared to a 10 µg (0.01 mg) dose, which showed a less dramatic increase in serum estradiol levels during the first 8 hours and no significant difference after 14 days when compared to placebo (P<0.01).12 See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Unadjusted mean serum estradiol concentrations after treatment with TX-004HR 10 μg estradiol vaginal inserts (n =19) versus placebo (n=17). Copyright © 2019 The North American Menopause Society. Used with permission from author.

Estriol (E3)

Estriol (E3) is present in small amounts in premenopausal women. It is the main estrogen produced during pregnancy, and it is made by the placenta. E3 is 1 of the hormones measured in a quad screen, a blood test used during pregnancy to assess the risk of fetal deformities.13 Estriol is the weaker estrogen. It has greater affinity for estrogen beta receptors (ERβ) and less affinity for estrogen alpha receptors (ERα).14 There is evidence that stimulation of ERβ can produce antiproliferative activity and that ERα is more responsible for the proliferation of breast tissue.15

Ultralow-dose estriol of 0.03 mg (30 µg) has been shown to help with menopausal symptoms related to vaginal atrophy and—when 100,000 colony-forming units (CFU) of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus are added—reduce recurrence of urinary tract infections.16,17 There was a trial using 0.03 mg vaginal tablets with 16 postmenopausal women with breast cancer who were also using aromatase inhibitors. These women inserted the vaginal tablet daily for 4 weeks and then reduced therapy to 3 times per week for a total of 12 weeks. Although there was a slight increase in serum estriol (E3) levels after 8 weeks, there was no rise in E1 or E2 serum levels.18

Between 2008 and 2011, a large trial took place involving 59 centers in Germany.19 This trial compared the use of 0.2 mg and 0.03 mg pessaries versus placebo for vaginal atrophy. Over the course of 12 weeks, estriol and placebo were given once daily for 20 days, followed by twice weekly for 9 weeks. Participants reported vaginal dryness as the most common symptom. Both the 0.2 mg and the 0.03 mg doses were more effective than placebo in improving signs and symptoms related to vaginal atrophy. The lower dose of 0.03 mg resulted in clinically significant improvements in the vaginal maturation index, and the pH of the vaginal area changed to a more acidic level of around 5.

Some literature suggests a relationship between higher pH levels in the vaginal area and increased risk of urinary tract infections.20 In addition, the loss of favorable microflora such as Lactobacillus species may increase the risk of urinary tract infections.21 In a study involving 132 postmenopausal women, researchers noted that there was a significant correlation between vaginal pH and vaginal atrophy symptoms (P<0.001). There was also a lower count of Lactobacillus species found in individuals with vaginal atrophy, which is associated with a reduction of lactic acid produced, thus increasing vaginal pH levels.22

If you use a compounding pharmacy for the estriol dose of 30 µg, be sure the pharmacy can compound such a low dose. This is more possible with orders of larger quantities. For example, with an order of 100 tablets or 60 grams of cream, it is more likely the pharmacy can create this low-dose formula. The pharmacy may also have the ability to add the Lactobacillus probiotic directly to the estriol formula.

Estetrol (E4)

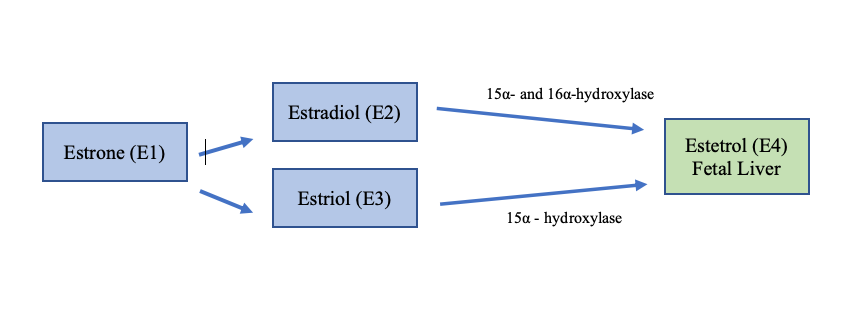

Estetrol is produced by a growing fetus, and it is produced only during pregnancy. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Estetrol is produced in the fetal liver and only found in low levels during pregnancy. Estetrol is converted from estradiol and estriol by the 2 enzymes 15α- and 16α-hydroxylase.

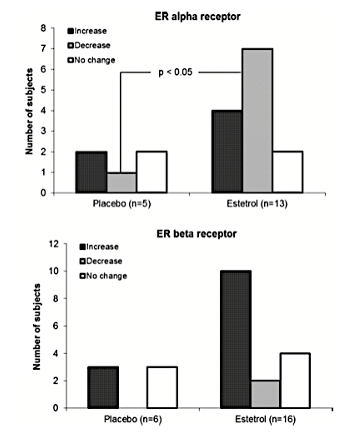

Although not a lot is known about this estrogen, research has shown estetrol to be 100 times weaker than estradiol, and it appears that estetrol is a weak estrogen agonist primarily through ERα and an antagonist to the proliferative effects on breast tissue associated with estradiol.23 In a small study of 15 women, using 20 mg of E4 resulted in a significant down-regulation of ERα and up-regulation of ERβ (P<0.05). See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Increase (dark gray bar), decrease (light gray bar), or no change (white bar) in intratumoral expression of ERα and ERβ in response to 14 days of oral treatment with 20 mg E4 or placebo per day.24 Used with permission from the authors.

E4 appears to not alter coagulation factors in the liver, which may contribute to reduced risk of thrombosis.25 In a 2017 study, it was shown that E4 decreased levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in a dose-dependent manner, which suggests that E4 has a negative feedback effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.26 This study also found that 10 mg of E4 had similar positive effects on bone turnover markers as a dose of 2 mg of estradiol. The bone turnover marker used in the study was osteocalcin levels, which have been shown to increase with estrogen deficiency–related menopause. A reduction in osteocalcin levels in the study is favorable to bone density in menopausal women.27

Because of E4’s high bioavailability and half-life of 28 hours, patients can appropriately use it as an oral agent. For contrast, E3 has a half-life of 20-30 minutes. E4, at a dose of 2 mg, has been shown not to be associated with endometrial proliferation.

The Role of Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a hormone produced by the posterior pituitary gland and perhaps is most noted for its role in stimulating the production of mother’s milk during breastfeeding. We now know that this hormone is associated with both male and female sexual function, as well as with promoting social bonding.28 In this article, we will focus on the use of oxytocin for postmenopausal symptoms.

Researchers administered intranasal oxytocin at a dose of 32 IU to a group of heterosexual females aged 41 to 64 years and diagnosed with hypoactive sexual desire, arousal, or orgasmic disorder. The study included the male partners, and couples were selected based on exclusion of those having relationship problems or male androgenic dysfunction. In this study, 63% of the women were categorized as postmenopausal. Although the female sexual function test was very slightly higher in the group using intranasal oxytocin as compared to the placebo group, there was no significant difference overall in the oxytocin versus placebo groups (P<0.01).29

The focus so far in this article has been to discuss low-dose alternatives for the treatment of menopausal signs and symptoms, primarily those involving the improvement of vaginal atrophy, vasomotor symptoms, and chronic urinary tract infections afflicting those in the menopausal-age group. The use of oxytocin instead of or in combination with ultralow-dose estrogen merits strong consideration. There is evidence that oxytocin stimulates the gastrointestinal tract, and it has been shown to enhance gastric emptying in response to meals.30 This review will focus on topical vaginal applications.

In a study involving 140 postmenopausal women (70 in the oxytocin group and 70 in the placebo group) and the use of 1 mg (600 IU) of oxytocin gel, 69% of the women using vaginal oxytocin showed a reduction in vaginal atrophy (P=0.001). In addition, 45 of the 70 women in the oxytocin group experienced a significant reduction in dyspareunia (P=0.001). It is important to note that there was no significant increase in serum estradiol levels in the oxytocin group.31

Interestingly, research demonstrates that estrogen stimulates the activity of oxytocin, and testosterone may reduce the effects of oxytocin, alternatively shifting its hormonal activity to that of vasopressin.32,33 Vasopressin may lead to overstimulation of the sympathetic system. So theoretically speaking, oxytocin, when combined with estrogen therapy, may have synergistic effects.

Another study compared intravaginal administration of 400 IU and 100 IU of oxytocin compared to placebo. There were 24 women in each of the treatment arms. In this study, the effects of oxytocin on pH, vaginal atrophy, and dyspareunia were evaluated. Interestingly, women using the 100 IU gel were found to have a lower pH than those using the 400 IU (P=0.0245). Women using 100 IU of oxytocin showed a clinically significant improvement in vaginal atrophy (P=0.005) and a reduction in dyspareunia (P=0.0156). The 100 IU oxytocin group did not experience an increase in endometrial thickness or increase in serum levels of estradiol.34

A topic of particular interest is the potential use of oxytocin in reducing the risk of certain cancers. Research has shown that breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer.35,36 Oxytocin receptors are also found in other areas of the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract and prostate; there is evidence that oxytocin might be protective against certain gastrointestinal cancers and prostate cancer.37 More research is needed before any recommendations can be made.

Micronized Progesterone

The final discussion needed when reviewing the use of estrogens in the treatment of menopausal symptoms is when to use (and when not to use) progesterone. Progesterone or progestins are used to oppose the potential effects of endometrial proliferation from the use of estrogens. In other words, when the use of estrogens causes the endometrial lining to thicken, progesterone should be used to counter this estrogenic effect. Other factors also increase the risk of endometrial cancer, including BMI and going into menopause at a later age, but consistent in the research is the fact that unopposed estrogen use is a significant risk factor.38

Gompel (2012) reviewed the use of 200 mg of micronized progesterone versus progestogens. In a study involving 596 postmenopausal women during a 3-year period, the use of micronized progesterone as compared to progestogens did not significantly increase high-risk endometrial changes (P=0.16). The author also noted that most studies concur that continuous use (25 days per month) of progesterone as compared to sequential use further reduces the risk of negative endometrial alterations.39

A study of 77 postmenopausal women compared the use of conventionally prepared conjugated equine estrogens (0.625 mg) in conjunction with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (5 mg) to natural E2 gel (1.5 mg) in conjunction with oral micronized progesterone (200 mg). After 2 months of treatment, the conventionally prepared estrogen/medroxyprogesterone group showed significant breast cell proliferation, whereas the group receiving natural E2 plus oral micronized progesterone demonstrated no significant increase in breast cell proliferation (P=0.05).40

Researchers also studied oral micronized progesterone (200 mg) for its effects on cardiovascular risk and found that when it’s combined with non-oral E2, there is no increased risk of cardiovascular complications such as elevated levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) or lipid levels (P<0.01 and P=0.1, respectively).41

Laboratory Evaluation

One challenge or obstacle in measuring estrogen levels (primarily estradiol) in postmenopausal women is the questionable accuracy when trying to evaluate low levels of estrogen. Though not related to menopause, this challenge is especially important in women with fertility issues or those using aromatase inhibitors, when detection of subtle fluctuations is needed for proper assessment. This challenge also arises when using low-dose or ultralow-dose estradiol therapy, and there is a need to evaluate between undetectable and very low plasma levels of estradiol. Accurately measuring serum estradiol levels might help the clinician determine compliance and evaluate the impact of specific dosing regimens for determining suitable levels of HRT on bone density, for example. Although evidence exists that increased circulating estradiol levels in postmenopausal women may increase the risk of breast cancer, clear clinical guidelines are lacking. Ordering measurements of serum estradiol levels prior to HRT might be of clinical value; however, this author recommends further clarification.42 Because the half-life of estriol is so short, ordering serum level tests of this hormone is of questionable value until more is known about the association between estriol and disease risk.

Delivery Types

Creams and Gels

HRT base creams should be an oil or oil-in-water cream free of polyethylene glycol, fragrances, dyes, petroleum, and parabens. Patients can ask that specific oils, such as coconut oil, be used, but the absorption may not be the same as an oil-water base cream. Several commercially available HRT base creams are available, such as HRT Heavy and VersaBase. VersaBase also comes in a gel form. The advantage for pharmacies in using some of these commercial forms is that the shelf life can be as long as 6 months. If the creams or gels have too high of a water content, the regulated shelf life might be only 14-30 days.

Capsules

Capsules can be inserted vaginally, though depending on the capsule type, women sometimes complain that the capsule does not dissolve. Oral micronized progesterone comes in a capsule form.

Tablets

A few compounding pharmacies offer vaginal tablets. The ultralow-dose estriol from Germany called Gynoflor is a tablet and has been on the market in that country for several years.

Summary

Any hormone replacement therapy should take place only in conjunction with open and honest dialogue with each patient. Medical practitioners must explain the potential benefits and risks and incorporate into clinical practice proper follow-up during the replacement period. As published in The North American Menopause Society’s position paper, HRT in breast and/or endometrial cancer survivors should be considered only after efforts have been made to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms with nonhormonal therapies, and this decision should be made in conjunction with the patient’s oncologist.43

When practitioners and patients are considering low-dose and ultralow-dose estrogen therapy, they should give the same consideration. The ultimate clinical and patient outcomes should reflect the thoughtful and evidence-based decision-making process of the physician who is also respecting the involvement of the patient in the process.

The monitoring of changes in serum estradiol levels is worth considering; it’s advisable for the prescribing physician or oncologist to check for changes in endometrial thickness as needed.

Estetrol and oxytocin offer unique and promising alternatives for practitioners, especially given their potential antitumor properties, although more studies are needed to verify the safety of these therapies. The use of progesterone to oppose estrogen therapy is a strong recommendation; however, sustained use of oral micronized progesterone (25 days per month) appears to best reduce the risk of endometrial problems. The use of progesterone in conjunction with low-dose and ultralow-dose estriol may or may not be required, but until more clinical trials are conducted, the use of oral micronized progesterone would have greater benefits and safety.

For women without any personal or family history of female cancers, HRT should center on offering the most benefits from therapy while minimizing any risks. Starting at the lowest dose of HRT to accomplish the highest degree of benefits should be the goal of the patient-doctor relationship.